Collections | Livre | Chapitre

Falling into extremity

pp. 82-101

Résumé

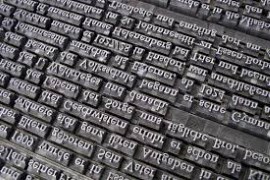

There is no such thing as "the sense of touch"; there are only senses of touch. As philosopher Mark Paterson argues, touch must involve much more than tactility or the receptivity of skin surfaces to pain, pressure, and temperature: it must also embrace proprioceptive matters such as one's awareness of balance and of bodily movements through space (2007: 3–5). Touch in this more capacious register may be described as "haptic," a word defined through its Greek etymology as meaning "able to come into contact with" (Bruno 2002: 6). To engage notions of the early modern haptic may appear anachronistic, for the word entered the English language only in the late nineteenth century as part of a specialized psychological and linguistic lexicon — the wider currency it has recently achieved in aesthetics, film theory, and architecture has to do with the modern science of haptics, which focuses on simulating touch and touch-based interfaces in virtual worlds. It is nevertheless true that early modern culture, no less than our own, recognized the entanglement of tactile and proprioceptive knowledge.

Détails de la publication

Publié dans:

Gallagher Lowell, Raman Shankar (2010) Knowing Shakespeare: senses, embodiment and cognition. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Pages: 82-101

Citation complète:

Cahill Patricia, 2010, Falling into extremity. In L. Gallagher & S. Raman (eds.) Knowing Shakespeare (82-101). Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.