Livre | Chapitre

Home truths

Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the house beautiful

pp. 145-159

Résumé

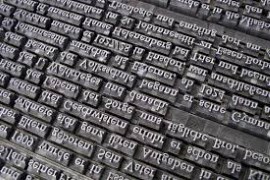

For Oscar Wilde, as later for Bloomsbury, the decorative or applied arts were paradigms of the purely aesthetic. Uncompromised by any representational aim, they rejoiced (so it was held) in their consequent moral and conceptual vacuity. In an ideological world such a view has undoubted attractions. It offers one a blessed, if temporary, escape from the despotic ubiquity of meaning. But nothing more obviously refutes it than the fact that people — and none more anxiously than its proponents — stake so much on what may seem to be minor aesthetic preferences. We may argue with a man about his reading matter, but to question his taste in clothes or furniture is the height of impertinence. His inner self seems to be much more closely implicated in them. Their semantic reticence, in fact, serves him as a much-needed existential armour. For there is an older critical tradition which asserts that the style, however inscrutable, is really the man himself. "Tell me what you like," said Ruskin ominously, "and I shall tell you what you are." And since no man is an island, our tastes reveal, not only ourselves, but also the society in which we live. Our interiors are documents, sometimes even manifestoes, of great cultural and political significance. The same is true of those very aestheticist doctrines which try to deny the fact. I propose to be inquisitorial about the meaning of interior decoration, and I shall take as my main text the domestic designs of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who is currently much in vogue.

Détails de la publication

Publié dans:

Grant Robert (2000) The politics of sex and other essays: on conservatism, culture and imagination. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Pages: 145-159

Citation complète:

Grant Robert, 2000, Home truths: Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the house beautiful. In R. Grant The politics of sex and other essays (145-159). Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.